FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum Announces Transformative Legacy Gift from the Late John Balushak

Brandon, MB — January 9, 2026

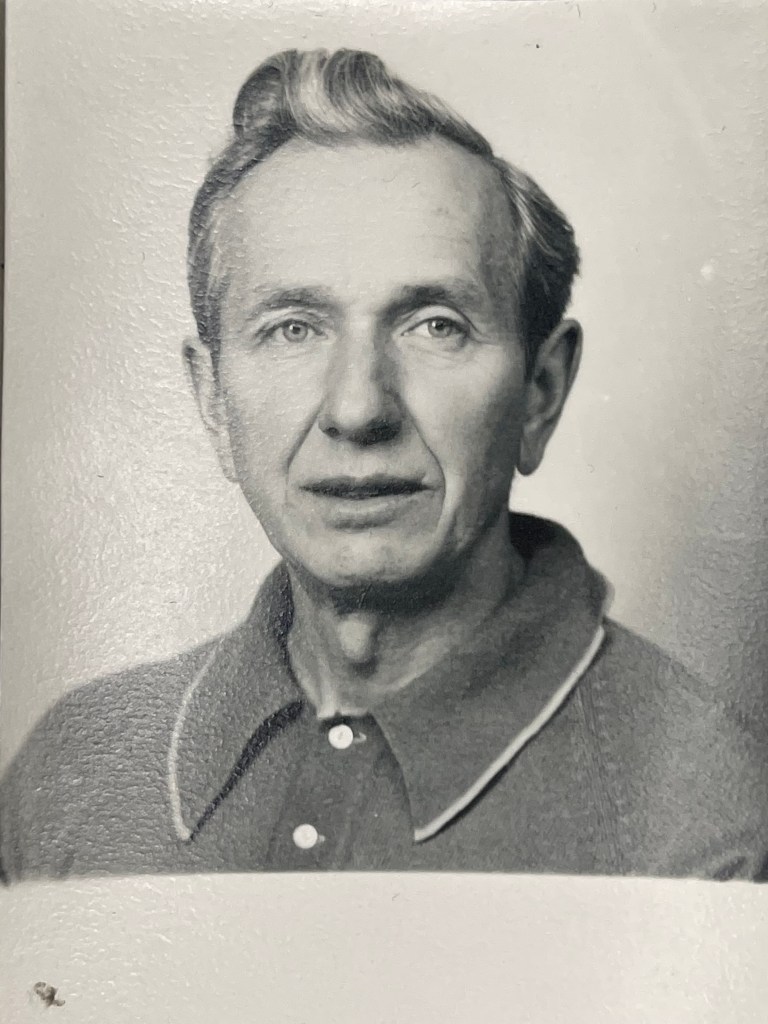

The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum (CATPM) is honoured to announce a remarkable legacy gift of $1.6 million from the late John Balushak, a long-time supporter, life member, and friend of the museum.

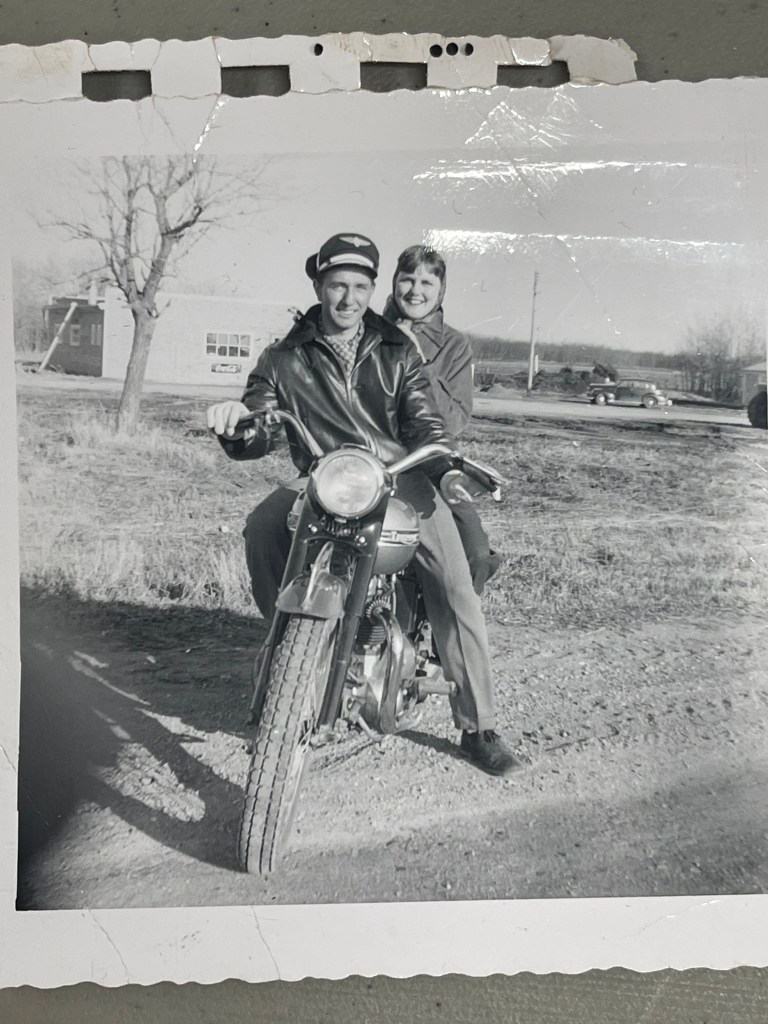

A retired engineer with Manitoba Hydro, Mr. Balushak passed away on March 22, 2024, at the age of 89. Throughout his life, he combined a love of engineering and aviation with a quiet commitment to preserving Canada’s Second World War history. Though he never sought attention for his generosity, his support of the museum was constant and heartfelt, his framed lifetime-membership certificate held a place of pride in his home, a quiet testament to how much the museum meant to him.

“John Balushak exemplified the spirit of the community that built this museum,” said Zoe McQuinn, Director General of the CATPM. “He believed deeply in honouring the service and innovation of those who trained through the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, and his legacy gift will help us carry that story forward for future generations.”

Mr. Balushak’s planned gift will play a pivotal role in the museum’s ongoing transformation, supporting the preservation of aircraft, archives, and training artifacts, and helping to expand educational programs that connect new generations to the story of Canadian service, resilience, and ingenuity.

Mr. Balushak’s legacy reminds us that even the quietest acts of generosity can leave a lasting mark. His passion for flight and history will continue to inspire everyone who walks through the museum’s doors. His gift ensures that his love of aviation and his belief in remembrance will continue to inspire for decades to come.

To learn more about supporting the important work of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum, or to make a donation, please visit www.airmuseum.ca or contact Zoe McQuinn, Director General, at DirectorGeneral@CATPM.onmicrosoft.com.